Admiral's Row, 1864-2016 evolved out of our artist residency at the Works On Water/Underwater New York project space on Governors Island in July 2019. As part of that residency, we created a video installation titled Shoreline Change with several of our short documentary films about New York's changing waterfront. One of those films documented the decay and destruction at Admiral’s Row, a collection of historic mansions inside the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Although the water was never visible through the forest that had grown up around Admiral’s Row during its years of abandonment, the homes there were a unique relic of New York’s nautical history, a history which is also reflected in the cracked walls of the former military houses on Governors Island in which we presented the film.

Read MoreOn the late July day that President Trump called my hometown a “rat and rodent-infested mess” where “no human being would want to live,” I found myself dumping 200 pounds of compost into a vegetable garden across the street from a Baltimore methadone clinic. The compost had been cooking in my backyard for almost a year and included a dozen large Hefty bags of leaves from our silver maple and black cherry trees and all the watermelon rinds, avocado skins, and broccoli stems my family of four had eaten over the last 12 months.

Read MoreTwo days before my due date, I executed a slow roll to get up off the couch where I’d been resting and felt a rush of water dampen my leggings. I’d had the same sensation earlier that morning when climbing out of bed. On the phone with the nurse though, I couldn’t confirm the word “rush,” nor the word “water.” Even so, she said, I’d better come in.

Read MoreThe American newsboy was born in New York. This was no chance occurrence. With a population of more than 200,000, “Gotham” was the largest city in North America. Its year-round harbor had long made it a bustling port, but the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 transformed it into a continental center of trade, finance, and manufacture.

Read MoreI learned a new word recently: rampike. A rampike describes a tree—a dead or dying tree. Rising salt waters make rampikes.

On a Sunday in late September I spent the day as I often do, moving shore to shore with Jonah, my seven-year-old son. Days are long, years are short, or so the adage goes, though both can stretch the bounds of the tolerable to me.

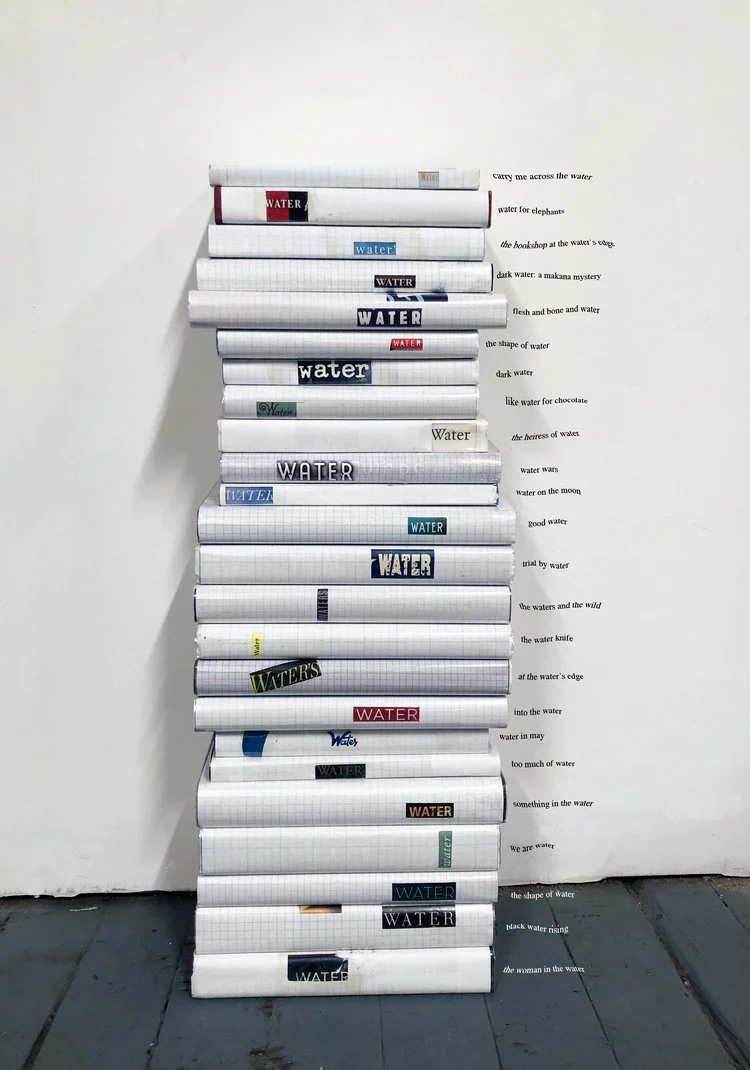

Read MoreElizabeth L. Bradley has contributed to Underwater New York, Salon, Smithsonian.com, and Gothamist. "Water" is excerpted from her new history, "New York," by permission of Reaktion Books, London, England (please note Anglicized spelling throughout). "New York" is available for purchase here.

I call out that I’ve found a bone, a spinal vertebra perhaps, and I begin to pull away the seaweed and sand crabs from where the marrow once was. The friend I've brought here appears at my side and I hand him the horse bone. He turns it over in his hand; it looks more like wood than bone from years of being tossed and aged in the bay. We keep pawing through the broken bottles and tinker toys littering the shore and find a very bone looking bone: long and thin in the middle and bulbous on the ends, like a dog toy or a bone you’d see in a cartoon. We are preoccupied with this carnal treasure hunt. We have done the remarkable: we have found a certain joy in death.

This work was created during the WoW/UNY Governors Island Residency. Micki Watanabe Spiller was in residence on Governors Island from May 21-June 24, 2018.

Read MoreThis work was created during the WoW/UNY Governors Island Residency. David Andree was in residence on Governors Island from June 25-July 8, 2018.

Read MoreI call out that I’ve found a bone, a spinal vertebra perhaps, and I begin to pull away the seaweed and sand crabs from where the marrow once was. The friend I've brought here appears at my side and I hand him the horse bone. He turns it over in his hand; it looks more like wood than bone from years of being tossed and aged in the bay. We keep pawing through the broken bottles and tinker toys littering the shore and find a very bone looking bone: long and thin in the middle and bulbous on the ends, like a dog toy or a bone you’d see in a cartoon. We are preoccupied with this carnal treasure hunt. We have done the remarkable: we have found a certain joy in death.

Read MoreIn the 1950s, US Navy submarines heard a strange underwater noise near Hawaii and southern California. A coiled chirping sound that sprang to a rapid crescendo, and then fell just as quickly. No one knew what it was. The sound became known as a “boing.” Scientists later guessed it was a whale, but it wasn’t until nearly half a century later, in the winter of 2002, when a boatload of researchers in the Hawaiian Islands finally heard a boing and spotted a whale at the same time. The boing remained a mystery for so long in part because its source is one of the smallest of the whales, one that doesn’t make a big spout and doesn’t surface for long: a minke whale.

This piece is a part of WATERFRONTS, a series of personal essays engaging with the waterways of New York and/or Los Angeles, presented in collaboration with Trop.

Read MoreMy idea for getting married on a boat in the Hudson River was, in theory, a good one. It had come to me in a flash one afternoon at Shelter Island where my fiancée Karen and I had gone to scout out possible venues for our wedding. We were hoping to have a ceremony that was simple and secular, quirky but classy, something that incorporated our abiding love and affection for New York City, and also something that didn’t cost too much. Most of these requirements, however, seemed to have little chance of being satisfied by what we had seen during our six hours on Shelter Island, and it wasn’t until evening, while the two of us sat on the shore, depleted and dejected, imagining the worst possible cookie-cutter wedding, that we happened to observe a sailboat serenely floating past.

This is how I remember it: From the park, you could see the sewage flowing out to the Hudson. The seagulls swooped all around the brown discharge. That’s the image: a cloud of gulls, rejoicing in our waste.

This fragment has two parts. The first splashes through the Hudson River one early morning this past September. The second will take place next week, on the Monday before Thanksgiving, inside the canal of my left ear.

Tell me about memory and distance and time. I don’t quite understand how they converge even now, pushing forty. I used to view distance solely in terms of time, used to think any trip that was an hour north was in the same place: visiting cousins in Bergen County, going on trips to museums in the city, venturing off to my dad’s office in North Brunswick. They were all in the neighborhood of an hour from my hometown and, being a child, I never looked at a map, never gleaned where they all were in relation to one another. I thought of everything with a flawed logic, without a sense of space or geometry. That was something I had to learn. It shifted when I went from passenger to driver, changing my relationship to the roads on which I traveled.

The evening skyline in late August looks cold from the High Line, but it’s 75 degrees with humidity. People are up here with me—the 22-year-old west coast naïf—but I’m the only one around watching the black sky and blacker water. A loud someone takes a photo to my right and the flash lingers, icy and white, when they walk away. I stand at the railing, pretending to look native, despite my backpack, and not clueless, despite the Google map I’ve got queued up on the phone in my pocket. I’m short a dad double-fisting a hot dog and a Big Bus brochure—which is my actual dad right now in our Times Square hotel.

Read MoreMy parents live in a small house on a narrow sliver of land that faces the rocky shore of the Long Island Sound and backs up to a marsh, home to swans, egrets, sandpipers and plovers.